No matter your age, gender or race, there’s at least two things that each individual has in common.

- We all have DNA.

- We each have a unique genomic makeup that we share with no other else.

For years, researchers and scientists have searched for different ways to turn genomic data into information that can give a glimpse into a patient’s health story through precision medicine.

Precision medicine, as defined by the National Institutes of Health, is “an emerging approach for disease treatment and prevention that takes into account individual variability in genes, environment, and lifestyle for each person.”

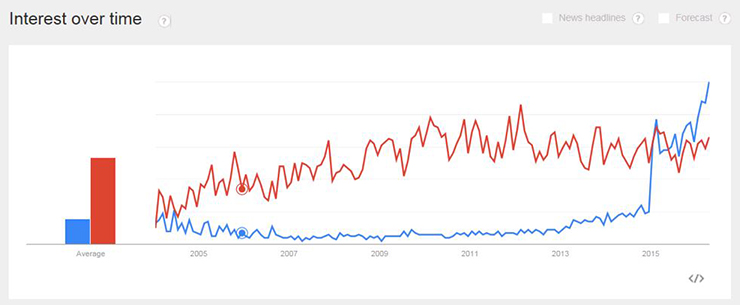

“While precision medicine is commonly referred to as personalized medicine, I think of the two terms differently,” said Matty Francis, director of innovation consulting at Healthbox. Francis studied biomedical engineering and has spent most of his career in the healthcare technology space. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), personalized medicine has seen a decrease in use, while searches for precision medicine have increased significantly.

“To date, both of these terms are often used interchangeably, but I believe it makes sense to segment them into two separate things – with precision medicine typically describing interventions for a specific population and personalized medicine more focused on an individual care plan,” said Francis.

Precision Medicine in Blue, Personalized Medicine in Red; Source: CDC

Though the terms are used interchangeably, Francis notes that it is important to understand the nuances between them. Using the term ‘personalized’ may imply treatments are developed uniquely for each specific individual, which isn’t always the case. Precision medicine is more focused on identifying the most effective approach for a patient’s care based on genetic, environmental and lifestyle factors.

“I think of it from a top-down approach: How can I target a population that has a certain condition and tailor the intervention to that particular population?

“A great example would be in cancer care. Historically they have named the type of cancer based on the organ where the tumor first appears – it doesn’t matter if it spreads to other areas of your body; if you observe it in the lungs first, it’s lung cancer,” Francis explained. “Not all forms of lung cancer are the same. So identifying a group of patients that have the same type of cancer that tends to appear in the lungs – that top-down approach I view as being precision medicine.

“Personalized medicine comes from the bottom up. You start with the patient, you take a look at their unique characteristics and everything from genetics to microbiome to their lifestyle and zip code. Then you can start to develop treatments for that particular patient.”

Francis noted that most of the work in precision medicine to date has been in cancer care, or oncology. “Cancer was the spot where they could make the most impact early on. These are highly complex patients who are often in the hospital for extended periods of time, so you’re able to take more time to design a better care plan.” Although testing for genetic mutations has already been a standard of care in lung cancer, only an estimated 9 to 15% of patients with advanced cancer are eligible for targeted therapies, Kaiser Health News reported.

“Step one is finding a way to collect that data. Step two, you need a place to store and transform raw data into information that is actionable. And that’s where organizations need to go,” said Francis. “Having the technology infrastructure to accommodate this data, and having the processing power to take raw data and translate it into a point where we can look at Patient A and determine what the proper course of treatment is for that particular individual.”

The Role of Genomic Data

Today, people have increasing access to their genomic data through direct-to-consumer genetic testing kits – one example of the many nuances between precision medicine and personalized medicine.

When direct-to-consumer kits first evolved in the 1990s, they were considered a luxury. “The price tag to sequence one person’s DNA was into the billions, and now you can do some tests for a few hundred dollars,” said Francis.

“What’s really compelling is a genetic testing kit’s ability to aggregate all of that data across the population of individuals who have taken their test, and they can then identify patients with a specific mutation – in a way there would just be no practical way for someone running a more traditional, clinical trial to do,” said Francis. Over the last few years, the popularity of these kits exploded and in 2017, the total number of people using them increased to 12 million.

Unsurprisingly, the CDC has expressed concerns about the health profile option bundled into many DNA testing kit packages, which they hope consumers will take with a grain of salt. Recognizing the importance of education and awareness, the CDC has made available public database resources like the Public Health Genomics Knowledge Base (PHGKB).

Preparing for the Next Chapter: Social Determinants of Health

“In precision medicine, so much focus has been placed on the genome or DNA and how can we tailor treatment for that,” said Francis. “However, there’s a whole other host of other data points that impact care, and I think that one that’s kind of having its first moment in the sun is social determinants of health,” said Francis.

Thirty years ago, physicians weren’t trained to ask patients questions about their access to things like food, shelter, water and transportation to medical appointments, Francis explained. “That’s starting to change as a new generation of physicians are coming out of medical school and residency. As they start to ask those questions, they can build more personalized care plans for these patients,” he said, citing fresh food pantry initiatives as an example.

Actionable outcomes are dependent on evidence-supported insights, and one major challenge facing precision medicine is ensuring data obtained is accurate and unbiased. Historically, social and behavior health data was collected through surveys and self-reporting. Today, many precision medicine programs utilize EHR data collected through patient visits to develop insights based on social determinants of health. But in order to leverage the data collected to support these insights, it must be easily retrievable – another major challenge facing healthcare.

“Unless these challenges are addressed, EHR-derived social and behavioral data could limit the usefulness and applicability of precision medicine research,” the American Medical Association warns.

In one documented case, seven patients treated for the same condition were told their disease was hereditary, which was later determined to be inaccurate. “Multiple patients, all of whom were of African or unspecified ancestry, received positive reports, with variants misclassified as pathogenic on the basis of the understanding at the time of testing,” the post-study report states.

As it turns out, genome-wide association studies have determined that 88% of the genomes are attributed to people of European descent, and that their genomic data is represented more than any other race or nationality in genetics research databases, despite not being the majority race or nationality worldwide. This opens up a wide margin of error.

As precision medicine continues to advance and evolve, ensuring the data collection process provides an accurate representation of all races and nationalities will be key to creating insights that are actionable.

In this HIMSS TV interview, University of Colorado Assistant Professor Mustafa Ozkaynak discusses the importance of addressing social determinants in the next phase of precision medicine and emphasizes the need for clinical decision support systems and tools that will integrate determinants into clinical data.

“The biggest trick is first earning the confidence of various clinicians to trust these personalized therapies,” said Francis. “When I put myself in the shoes of a physician who has undergone extensive training and has decades of experience treating patients; if someone walks into a room immediately suggesting an algorithm’s recommendation over my years of professional experience – that would probably be a short conversation.” Finding ways to partner with doctors throughout the development process goes a long way toward building that credibility, he added.

“It’s still a developing area of both science and technology so it’s not perfect. It’s important to take all of this with a grain of salt. There will be other factors and it’s not a perfect science at this point. And it might never get there, but it’s certainly getting better.”

Discover How Healthbox Ignites Innovation

Healthbox, a HIMSS Innovation Company and healthcare advisory firm, drives innovation from the inside and out, helping organizations build internal innovation programs, assess the potential of employee-led projects and look to the market to find solutions to implement or invest in.